Weekend Reads brings you longform features from Honest Cooking’s first iPad Magazine, which you can download for FREE here.

By Jackie Dodd

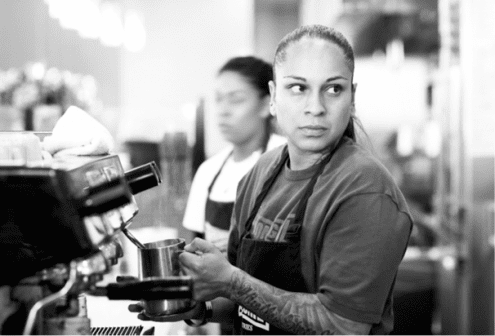

“Food is redemption,” says Erica, the kitchen manager for The Homegirl Café as she details the flight her entire crew has taken from incarcerated gang members to culinary professionals. “When you eat the pesto, it’s not just sauce. It’s basil we grow [in Urban Gardens] that taught a girl she had skills to offer the world, that there was more to life that she could be a part of. It’s not just pesto, but someone who has learned a skill, a new path. The stories are intertwined with the food. Anyone who eats here can see that.”

As she continually pushes non-existent crumbs off the table and into the palm of her hand, her dark hair pulled back into a neat braid, Erica explains how far some of the girls she works with, all ex-cons with a history of gang involvement, have come. “We have one girl, man we’re so proud, she just started an internship at the Bouchon kitchen, with Thomas Keller!” An incredible feat for any aspiring chef, but to the Homegirl Café grad, it is nothing short of a miracle. Homegirl Café is just one of the social enterprise programs, most of which center around the culinary arts, that Homeboy Industries uses to transform felons into thriving members of the community.

Dee, a recent addition to the Homegirl Café team has been working the line for about three months, coordinated by her parole officer just after her release from jail. “I love it here, they gave me a job when no one else wanted to work with the felon.” She spreads house made bread with mayo and continues to gracefully assemble a sandwich as the lunch rush, a mix of locals and suit wearing business types, pour in. “I’m working on my GED and I plan to go to college after that.” Her three kids, ages 8 to 20 have seen an improvement as well, with her regular home cooked dinners, steady paycheck and GED prep courses well underway.

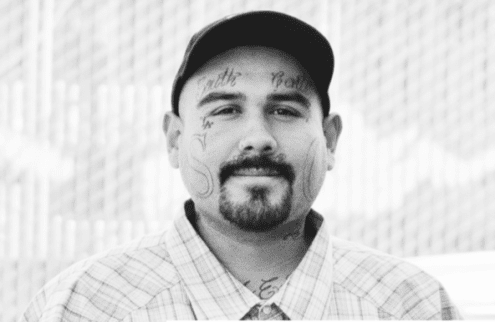

Outside the café two members of the Homeboy crew chat, “I’m getting the tattoos removed from my face.” Both men are done with work for the day but the Homeboy Industries headquarters has a relaxed accepting atmosphere, welcoming them to stay onsite as long as they like, and they do. A shy smile spreads across a heavily tattooed face that speaks to a life he is struggling to free himself from. “Homeboy will give me a job, but without that…you think anyone wants me?!” His laugh is genuine, and so is the pain behind it. Just three months out of jail, he is working with the janitorial staff and waiting for a position to open at the Homeboy Bakery. “They let me work my shift, run up to my tattoo removal appointments and then go right back to work…and I’m working on my GED here too. I’m gonna get that.”

His companion, Quran, has no visible tattoos, but employment has been just as hard to come by. “I’m back for the second time.” Just three days out of jail he has returned to the program for his second chance at a second chance. “I made a real big mistake, but I’m back. They’re like a family here, except everyone believes in you.” He proudly holds up his Homeboy Industries t-shirt and gives a list of ways the Homeboy team is helping him. In his manner, there is what appears to be fresh hope, possibly the first time he has not just been allowed to feel it, but encouraged to.

For the more than 160 members of the Homeboy employment program, it’s more than just a job. Along with two cafés, a bakery, a catering company, and nearly two dozen Farmers Market booths each week, Homeboy Industries also offers their team of men and women GED prep courses, Urban Gardening certification programs, mental health services, educational classes, parenting classes, legal services as well as a host of other services all aimed at a comprehensive answer to the problems that led them all to incarceration.

The food is at the center of it all. “It’s a healthy contemporary take on traditional Mexican with a focus on organic, local and in season produce, most of which we grow,” explains Erica. The healing effects of the urban gardening can’t be overstated, and were recognized early on, when the program first started. Several gardens are spread across the Los Angeles area, one of which takes up residence in a rough area punctuated with gang violence. “I was there with one of our girls not too long ago, who used to live in that area. She was so transformed by what was happening, she said, ‘This is a neighborhood where my friends used to take life, now it’s where we plant life.’”

The urban gardening program echo’s the simple but powerful message of Homeboy Industries: Grow, Prep, Serve. Not just a set of instruction for food service, but for a life transformation. Grow: plant and harvest herbs and produce, as well as grow in an understanding of who they are and how valuable they can be; grow themselves as people. Prep: prepare healthy, delicious food and prepare themselves to be valuable member of the world. Serve: serve food they are proud, and serve their community and their family. May sound trite to some, but the feeling of value and importance is one that so many of these men and women have never felt, that in itself is transformative, and with a program that is touted as the most successful in the country, it’s working.

Started in the 1980’s by a man that can fit no other description than Modern Day Saint, Father Greg Boyle has transformed a community. “Blow it up,” he says as he hands out his personal cell phone number to even the most hardened criminals he meets, and they do. Always greeted with love and the endearing terms of “Son,” “Mijo,” and “Kiddo.” Homeboy Industries has a success rate of near 80%, while the national average for gang rehabilitation programs sits somewhere closer to 20%. Father Boyle, a Jesuit Priest, never had the goal of creating the most successful gang rehabilitation program in the Nation, possibly the world. He hadn’t planed to be a sought after source of wisdom and inspiration, he just wanted to “invest in people rather than endlessly try to incarcerate our way out of this problem.”

The program began as a job skills training school, and a way to help felons find work once they left prison as well as nurture them into the people they could have always been. After realizing that work was hard to come by for the recently freed, Father Boyle decided to cut out the middleman and open a bakery, staffed with his “Homies.” The men and women that, even if they wanted to turn their lives around, wouldn’t even be able to find work at McDonalds. “They’re not natural-born criminals,” says Father Boyle, who looks more like an off duty Mall Santa than the leader of the largest gang rehabilitation program in the Nation, “They’re just out of options — no jobs in sight, dysfunctional schools and families, no sense of belonging in society.” He talks of a reality that the majority of the United States can’t even fathom. Born into gangs and crime riddle neighborhoods that witness violence and death as a daily rule, breeding people with a lethal absence of hope. He not only seeks to install that missing hope, with something as simple as kneading loafs of sourdough dough bread, he wants every soul to know they matter. “No life is disposable.” He watches as gang members, once running the streets in crime sprees, grow into a life filled with promise, careers, marriages, stable homes, children and a true sense of existence. “Nothing Stops a Bullet Like A Job,” their shirts read.

It may have been a coincidence that Father Boyle chose food service to help get the recently incarcerated back into society, or maybe he knew that the kitchen has always been ahead of the curve when it comes to social acceptance. Chefs don’t care if you’ve been behind bars, as long as you can work your station. No one in the kitchen minds if your face is tattooed and you live in your car, as long as your knife is sharp and your work ethic is strong, they are happy to set up a mise en place next to you. This is the environment that Father Boyle felt comfortable leaving his “Mijos” in. Father Boyle speaks frequently about the boundless gravity of kinship, “There is no ‘Us and Them’ there is only ‘Us,’” lending and even greater significance to his decision to center his endeavors around food, the one true common thread that every culture shares. Regardless of race, religion, class or country, we all eat in community, break bread with others, and share meals. Food is both sacred and unifying.

Father Boyle keeps the imprint of all the “Homies” he meets on his soul, reaching in for “Homeboy Parables,” whenever he is asked. He talks about a Christmas, not long ago, when six former gang members who had all been rejected by their families when they broke free from the gang life, decided to get together and figure out how to make a roasted turkey. “Ghetto Style,” is how the host of the gathering describes his cooking method: rubbed with a stick of butter, juice from two lemons, and “a gang of salt and pepper.” Those six former gang members, once bitter rivals hell bend on putting bullets into one another, sat in the kitchen, talking and laughing, as they stared at the oven until the turkey was done. “It tasted proper,” they had reported to Father Boyle. Retelling his parable, pride beaming on his face as he paints a picture of the once hopeless men grappling their way to a better life, his admiration is clear, “That’s what this is all about, that’s as sacred as the Last Supper.”

At the Homeboy Bakery Farmers Market booth set up on an overcast Tuesday afternoon at the USC campus, patrons wander by and watch a Homeboy employee cut up samples and answer questions, her dark hair secured in tight corn rows. She has been with Homeboy for 6 months, putting in hundreds of hours at the bakery before being promoted to the Farmers Market booth. “I loved the bakery, but I like it here better. Being with the people and telling them about the bread and pastries.” She recommends the Chocolate Chip cookie that would make even Jaques Torres proud and cuts into a freshly made ring of garlic bread, the cloves perfectly caramelized on the surface. When asked if anything surprises her about working for Homeboy she says, “How nice people are to me.” Not just the staff, who believe in every inch of who she can be, but the patrons of the booth she expertly manages, and the feeling of community in places she couldn’t have imagined while in jail. She has an easy way about her, if a bit timid. She is a strong woman, starting over and trying to find her footing in an unfamiliar world. She answers questions easily as each of the items for sale, baked fresh each morning by two shifts of baking ex-cons, are items she spent months making with her own hands. “They teach you a lot. You learn so much.”

Glenda takes a short break from her regular duties at the Café to talk about how she came to Homeboy Industries in her teens. “I wasn’t working, I wasn’t going to school…and then I made a mistake that changed my entire life.” Once she was released from jail and off house arrest, facing a seemingly insurmountable restitution payment, a chance encounter with Father Boyle changed the track she was on. “He just looked at me and said, ‘Hi Kiddo, what’s wrong?’ and when I told him I couldn’t’ find a job to pay back the state, he said, ‘Come back on the first, you have a job with us. You’re hired.’ He didn’t even know me and he gave me a job. I couldn’t believe it.” Five years later she now trains other men and women to work in the kitchen. “They MAKE you think you can do better for yourself,” her admiration for the Homeboy staff is apparent as she talks about the people who have surrounded her for the past half decade, “They stop you and say, ‘Hey, why don’t you do THIS instead of going backwards?’”

She’ll stay in food, she says. She has fallen in love with the process of making food with her own hands and has brought that love into her home kitchen where she teaches her young son how to make blended beans from scratch. “In the future I see myself in an even better life with my son, but still working with food and people.” With a shy smile you can see what her bones are made of, nurturing, compassionate, content but motivated, and extremely grateful for the life she has carved out for herself with an emotional pickaxe, handed to her by Father Boyle, and held up by a kitchen full of felons.

This piece was originally featured in Honest Cooking’s first iPad Magazine. Download the magazine for FREE here.

Culinary expression is certainly better than violence. This program is doing it! Thanks for sharing