Weekend Reads brings you longform features from Honest Cooking’s first iPad Magazine, which you can download for FREE here.

By Maya Parson

Just before I bit the balloon, the server — a young Erik Estrada with the decorum of a British butler — advised me to remove my glasses. Obviously he knew what was coming. Seconds later I was standing in the Alinea kitchen with sticky apple taffy on my nose, chin and lips, and lungs full of helium. “Oh my God!” I chirped in my best Alvin and the Chipmunks, “that’s amazing!”

The balloon’s creator, Alinea chef du cuisine Matt Chasseur, observed me with mild amusement and handed me a warm washcloth. I felt like a moron, but my childlike glee was exactly what Alinea chef and owner Grant Achatz had in mind when he set out to redefine our understanding of the restaurant by putting sensory experience and emotional connection at the heart of fine dining.

“What we’re trying to accomplish,” Achatz says in an interview with AOL, “is to pull people out of themselves, to make them have a great time, to make them laugh.” Eating at Alinea is “not about being buttoned up in a tight tie and sitting upright with great posture. It’s about kicking back and remembering your childhood and laughing with your dining companions and having fun.”

Eating a balloon — even the string is edible — is undeniably fun. But Alinea is also one of the most serious places to eat in America—a mecca of fine dining with formal service and a reputation big enough that there is no sign, only a man in a dark suit at the entry with an iPad that you pray has your name on it. (Scoring a table is notoriously difficult.) This is not Medieval Times or a Las Vegas all-you-can-eat buffet. Fun at Alinea is serious business.

That tension between the formal and the playful is just one in a long list of contrasts that Achatz artfully manipulates to make some of the strangest, most innovative and most remarkable food on the planet.

My party arrives to dine at Alinea on a weeknight in mid July. It is still hot at 9pm and passersby linger to chat on the sidewalk near the restaurant, a modern two-story grey box in Chicago’s upscale Lincoln Park neighborhood. After checking in with the man at the door, we enter a dark and narrow front hall lit only by a faint blue light. My heels sink into a thick carpet of live grass. To our left is a metal trough—the kind used to give water to farm animals—with punch cups bobbing and tinkling like chimes. Inside each cup is a taste of lemon slushie—sweet, tart and unexpected. Our evening has just begun, but already it is strange, exciting and yet familiar—a sort of Midwest summer evening in the Twilight Zone.

Near the end of the hall we find a door and step into the restaurant proper. What we encounter is also disorienting: no foyer, no central dining room, just the kitchen to our right and diners partially hidden behind curtains. With courteous efficiency but little fanfare, we are ushered upstairs like theatergoers arriving to a performance already in progress.

Our table is in a small and elegant but understated room. The walls, chairs and carpet are all beige. The mahogany tables and velvet benches are black. But along one wall is a profusion of hot pink orchids in aqua vases.

The first dish at the table is a small black plate of orange steelhead roe with coconut “pudding,” carrot custard and yuzu curry. The roe is rich and unctuous, bursting with the briny flavor of salmon. The dish is simply beautiful and it is suddenly clear why the décor is muted and the clientele obscured from view: the food is the one and only star of this show.

So far, however, I am not “kicking back…and laughing…and having fun.” The formality and intensity of the restaurant feels uncomfortable and I find the gaze of the servers — attuned to every detail of our movements in a way that I have rarely experienced in other fine dining establishments — unnerving: There are four or five people attending us at all times. Every wine glass is refilled seconds after the last sip. The place settings are whisked away the moment we have stopped chewing. At one point, my napkin slides off my lap and before it hits the floor there is a server at my side handing me a clean one.

Then, thankfully, comes the ice. An enormous block of glistening ice on a tray of rocks positioned with a sly smile from the server in the middle of the table. We are told that the chef “likes centerpieces.” Inside the ice, four holes the shape of laboratory beakers at odd angles, each one filled with a bright yellow or red liquid. It is weird — so weird it is funny. It is the ice that breaks the ice. We laugh (quietly, of course, this is still Alinea) and slurp collectively from glass straws.

And there it is, that strange-familiar thing, again. We are drinking watermelon, red and yellow — from a giant ice cube. I think I am starting to catch on to what Grant Achatz is up to. But even better, I am starting to have a lot of fun.

The next courses — a sublime series of riffs on shellfish with flavors ranging from shiso and soy to passionfruit—come on a “tray” of wet ocean wood covered in ropey seaweed. It smells and looks like the sea and I am, in fact, transported back to my childhood on the Long Island Sound. And I am chuckling to myself with pleasure because I have never, ever imagined eating lobster with carrot cream and chamomile foam, and it tastes fantastic. Strange-familiar, strange-familiar…It is at that moment that Achatz has reeled me in.

A typical meal at Alinea is more than twenty courses, eaten over four hours. Each course delivers Achatz’s mash up of the strange with the familiar like a one-two punch: One to the gut, one to the heart. Just like that, Achatz knocks you out, takes your breath away and keeps you coming back for more.

So much more that by the end of the night one of my dining companions comments that he feels as though he’s eaten the film equivalent of a triple feature—each one a prize winner to but sure—and he can’t keep the story or the characters straight.

In an interview, Achatz tells me that his creative process begins with storytelling — a conceptual narrative that motivates and links the courses together: “A lot of what we do, we’re trying to tell a certain story…[Storytelling is] the backbone. [You write] your tasting menu like somebody would write a storyboard for a movie or…an outline [for] a novel.”

Does it matter if we don’t follow the plot? Or understand every scene?

Achatz recalls with pleasure how one night a woman in her 80s came to Alinea for her birthday and began to cry when she was served a dish that included burning oak leaves — a concept rooted in Achatz’s own childhood memories of fall in the Midwest.

But Achatz knows that not every diner will connect this way with his creations — diners come to Alinea from around the world, from Germany, Japan and beyond. For most, he says, “there’s a difference between enjoyment [of the food at Alinea] and [its] creation.” In other words, while Achatz finds “immense satisfaction” in creating dishes that have personal meaning for him, this is an impressionistic fable, not an expository essay: “the intent [is] to make people feel however they want to feel” — to evoke emotion and pleasure, something Achatz certainly succeeds in doing.

In fact, Achatz seems a bit perturbed by clients who presume to know exactly what he has in mind when he creates a particular dish. He compares it to art critics describing a painter’s motivations: “You know, what always bothers me is that you have somebody like Chagall or Picasso or Rembrandt and you look at the painting on the wall and there’s that little plaque and it seems so pretentious, that whoever wrote that plaque says ‘Here, the artist’s intent was…’ and I always go, ‘the guy died 250 years ago, how do you know what his intent was?’”

Achatz adds, “I think he was painting that for himself…You know, people get all caught up in this art thing and they think that they know what people are trying to convey to them and sometimes we just create. We don’t even know why we’re doing it.” Diners, he emphasizes, don’t have to understand the creative vision behind each dish for the food to captivate them. “We’re ok,” he says, with letting people formulate their own opinion.”

At times, however, formulating your own opinion at Alinea is like wandering through a forest without a map: bewildering, a bit intimidating, full of unexpected oddities and delights. The menu only comes after the entire meal is finished and the servers offer only minimal — though sometimes surprisingly strict — guidance.

One course is a tiny squid perched on the tip of thin metal prong. It arrives at mouth level, tentacles levitating — more floating food. I reach out to touch it and Erik Estrada chastises me with a bashful grin: “Chef says no hands!” We lean in under the watchful gaze of the servers and bite.

The flavors are like fireworks: a dominant bitter charred taste, bright flares of orange and fennel, but the texture, in contrast, is tender. Only later do I discover that this dish is, in fact, as much “turf” as “surf”: On the menu, it is called Woolly Pig, a reference to the Mangalitsa pork it apparently also includes.

Another course we are served is more like a sculpture built by woodland sprites than anything resembling a plate of food: A platform of burnt wood supports smooth black river rocks. On the rocks, we find a special kind of morel mushroom, which, we are told, only grow in areas burnt by fire. Curious bits and pieces of food surround the morels—wisps of fried arugula, an unidentifiable soft rectangle that seems to be coated in crushed nuts, slivers of meat and a soft white blob a bit smaller than a quarter. (Eating at Alinea is not for the picky or faint of heart!)

I pick up the blob and put it whole in my mouth. It is liquid and warm on the inside, with a rich mouthfeel. I like it. But I still don’t know what it is. I ask the server to tell me what I’ve eaten and I get the sense that I am breaking the rules. I am the student asking an impertinent question of the professor in front of an entire lecture hall, but I get my answer: a quail egg.

I’ve never eaten a semi-liquid quail egg before— let alone a dish that looks like it was built on the forest floor, but there is something familiar in the sensation. It is only when I ask Achatz how he makes food that is both familiar and strange that I realize that the dish is a distant cousin (once or twice removed, no doubt) of eggs with ham, mushrooms and greens.

Achatz explains to me that he tries to make sure that there is something in each dish that people can relate to, even when the dish otherwise goes far beyond the familiar. This often means manipulating familiar ingredients and flavors— like eggs and mushrooms — in unexpected ways. For instance, he says, consider a common deli staple, the “everything” bagel.

“It’s got sesame seeds and onion…salt, pepper, you know, the whole shebang — and you put some cream cheese on it and, maybe, if you’re lucky, you put a little smoked salmon on there, and it’s delicious…I look at that flavor profile and I go…I’m going to recreate the everything bagel with smoked salmon in a way that people would never expect [so] it looks nothing like an everything bagel and when you put the plate down in front of somebody, they go ‘what the heck is that?’ and in that first bite, they go ‘Oh! That’s an everything bagel.’ Or, maybe that light bulb doesn’t go off, but it’s comforting to the brain because it’s somehow familiar to them.”

Achatz manipulates ingredients, textures and flavors with the help of high-tech gizmos (like his custom-made “anti-griddle,” which instantly freezes foods to super-cold temperatures) and chemicals (like sodium alginate, a kelp derivative used to create spheres of liquids), deconstructing familiar foods into their primal elements and recreating them into something unexpected and magical. A piece of what appears to be tofu, for instance, turns out to be a melt-in-your-mouth square of scallop. But these devices and techniques, Achatz is quick to point out, are tools that allow him to advance his art, not an end in themselves. Achatz dislikes the label molecular gastronomy, preferring to call his food “progressive American cuisine.”

Toward the end of our meal, a long stick of smoking cinnamon emerges from the kitchen. At one end of the stick is a lump of juicy Anjou pear with onion and gooey cheese under a layer of fried batter. Sweet, savory and intensely satisfying, it is like tempura had a collision with brie en croute. It manages to taste refined, exotic and kind of like junk food, all at the same time. We gobble it up in one or two bites.

Of all the contrasts that one encounters eating Grant Achatz’s creations, perhaps the most surprising is that despite the artful extremes, high tech sorcery and the exclusive price tag, this is not pretentious food. Achatz’s dishes may smoke, float and look like art installations, but nothing here is phony or shallow. Achatz takes you through a Technicolor Oz only to remind you of what’s already there in your own backyard. Emotion is his secret ingredient. As he puts it, “I think that’s the most powerful thing. If you leave that out of the equation, then you know what you have? Just food.”

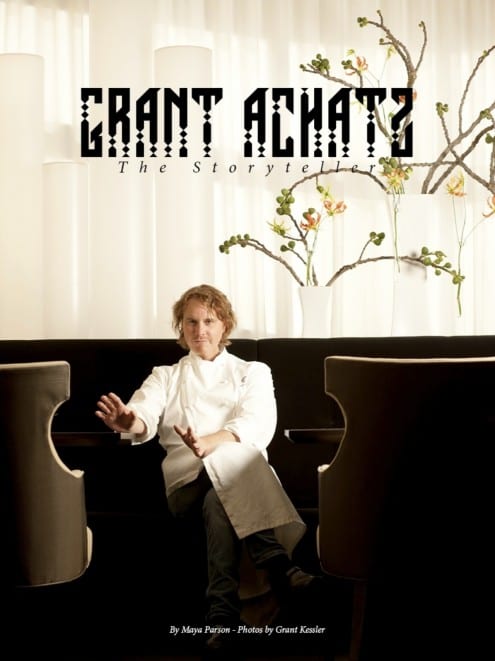

In person, Grant Achatz is as delightfully strange — and surprisingly familiar — as his creations. He walks around with a giant tweezers in his lapel (to position citrus peel and other minutiae on the plate) and talks about food and art with the erudition of a scholar, yet his tone and informal demeanor make him seem more like one of the locals at a home town hockey game than a culinary superstar. His voice is soft and raspy with a slight Michigan twang — he grew up in a middle-class family northeast of Detroit — and his speech is littered with colloquialisms like ‘gonna,’ ‘you know?’ and ‘like.’ Under his white chef’s jacket, he wears a pair of old blue jeans. His hair is scruffy and his eyes twinkle like you and he have an inside joke. Like his food, Achatz is a study in contrasts: intense and laid back, cosmopolitan and small town, prodigy and average guy.

For all these reasons, chatting with Achatz is disarming. When we sit down to talk in the Office, his private speakeasy at Aviary (the bar he opened alongside his newest restaurant, Next, in 2011), the conversation turns easily from the food at Alinea to reality TV to eating out with kids (he has two boys). You half expect him to pop open a couple beers and kick back, but slowing down isn’t in Achatz’s vocabulary.

When Achatz was diagnosed, at the age of 33, with stage 4 squamous cell carcinoma of the mouth, he just kept working, pausing only as needed for the chemotherapy and radiation treatments that saved his life—and, incredibly, his tongue. The doctors, he says, warned him to get his life in order in anticipation of his passing.

Achatz says he said to himself, ‘If you’re gonna die in six months, what do you need to accomplish?’ And the answer was a no-brainer: “I need to go to work.” He only stopped coming in to work toward the end of his treatments when his business partner, Nick Kokonas, told him that he looked so bad that he was going to scare the customers.

As he details in his bestselling memoir, Life, On the Life (co-authored with Kokonas), Achatz has worked pretty much nonstop in the food industry since childhood, beginning in his parents’ family-style restaurants where he moved up the ranks from dishwasher to line cook. After high school, he enrolled in the Culinary Institute of America, a path that took him from small town Michigan to New York City, the Napa Valley (where he worked under the tutelage of his mentor chef Thomas Keller at the French Laundry) and eventually back to the Midwest, where he was hired as executive chef at Trio (Evanston, IL). Achatz opened Alinea in 2005, followed by Next and Aviary in 2011.

I ask Achatz what his future holds. He’s not willing to share specifics just yet, but like the famous Chicagoan before him, Achatz clearly subscribes to Daniel Burnham’s dictum “make no little plans.” He and business partner Konokas are talking, he says, about new restaurants, museum exhibits, forays into film and television, food trucks and more. Whatever they do, Achatz says, “It won’t be a carbon copy of anything. It will be something completely original.”

Completely original and yet strangely familiar, that is.

This piece was originally featured in Honest Cooking’s first iPad Magazine. Download the magazine for FREE here.