Chef Tohru Nakamura blends his dual German Japanese identity into a cuisine so unique that brings together the best of both worlds. With an early passion for cooking, he trained in renowned European and Japanese kitchens and built a celebrated career in Germany. He is now at his pinnacle at the two-star Michelin restaurant Tohru in der Schreiberei, where every detail is thoroughly crafted to touch the heart of his guests.

Food writers, or anyone for that matter, have their own ideas of how things should be. For modern palate explorers, expectations or prejudices act as a compass, helping to determine whether a particular dish looks, smells and tastes the way it should, whether a dining experience is well directed, whether a restaurant has everything in its place or not, and so on.

But sometimes the compass doesn’t work. What do you expect from a restaurant in the oldest townhouse in Munich? The dream of a German-Japanese chef who cooks neither Japanese nor European cuisine?

Tohru Nakamura, the chef behind Tohru in der Schreiberei, defies many clichés and has somehow managed to create a unique style that has earned him two Michelin stars, 19 over 20 Gault & Millau points and the German Gault & Millau ‘Chef of the Year’ award in 2020.

And while Munich may not seem the hottest foodie destination in the world, it turns out to be a great culinary destination including a fairytale fish farm, a country estate dedicated to conscious butchery, the most delicate gardener and a wonderful restaurant that blends cultures and flavors with few, if any, echoes of other restaurant cuisines.

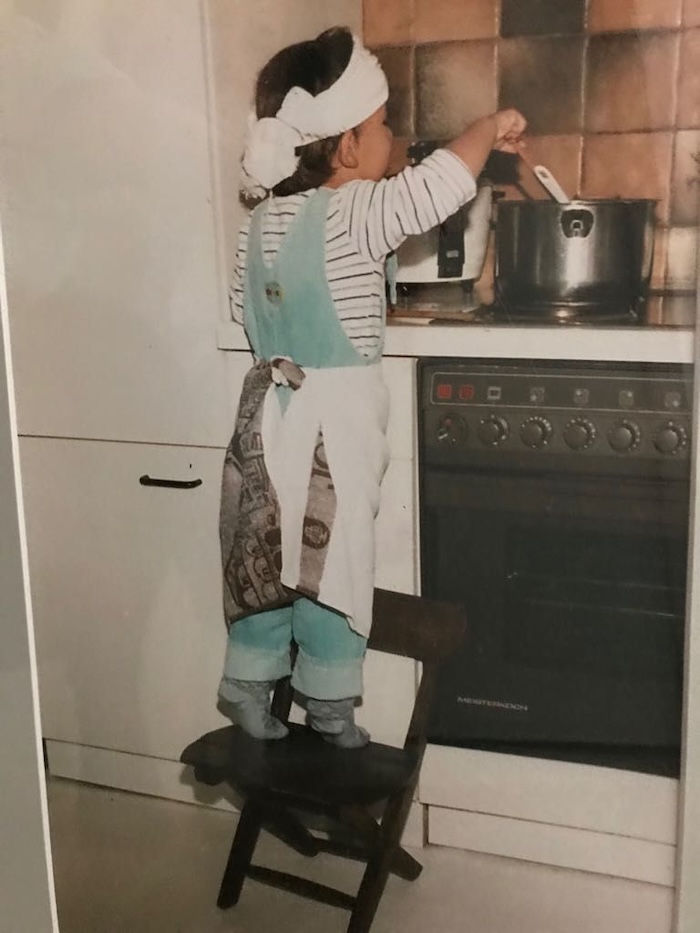

The 4 Year Old Cook

Born in 1983, Tohru Nakamura is not the fruit of a family tree with a culinary pedigree. Instead, he is the only son of a Japanese engineer and a German consultant who raised him with the expectation that he would become a diplomat, but from the age of four it was clear that Tohru’s had his own ‘honne’. The Japanese term ‘honne’ refers to a person’s true feelings and desires. ‘Honne’ is opposite to ‘tatemae’, which refers to the behavior and opinions one displays in public based on what is expected by society and required according to one’s position and circumstances. When ‘honne’ and ‘tatemae’ are not aligned, conflicts will naturally arise.

Tohru Nakamura’s ‘honne’ was always clear and strong. His parents taught him culinary values and the joys of sharing meals, often as a reward after hard sessions of homework or during weekends spent at the Japanese school he attended as a supplement to his German school. These moments of bliss inspired young Tohru to imitate his mother, a German who loved to cook the Japanese recipes she learned from her mother in law.

One of Tohru’s earliest pictures shows standing on a stool in front of the stove, cooking. His first words in Japanese were to order food when he was on holiday in Tokyo. And even when his father tried to set up the perfect scenario for his son to get a job in the diplomatic world, he had to give up after a 14-year-old Tohru ended up preparing breakfast for the Japanese ambassador in Denmark instead of asking to be his apprentice.

After his capitulation, Tohru’s father helped his son follow his dream by getting him a stint as an apprentice at Léa Linster’s restaurant in Luxembourg. So already at 14, the young chef-to-be was peeling potatoes in a one-star Michelin restaurant and loving every second of it.

At the age of 20 Tohru started his formal training. He went through tough and demanding hotel kitchens in Germany and ended at two three-starred Michelin restaurants, Vendôme, and Oud Sluis in the Netherlands where he became a sous chef and met Dominik Schmid “Smitty”, who became his squire in future culinary adventures.

Tohru then spent eight weeks in Japan. There he had the chance to explore his heritage, working at Sushi Ito and Hassun. But it was at three Michelin-starred Kagurazaka Ishikawa, that Tohru may have found his culinary cornerstone.

Back in Munich, Tohru became head chef at Werneckhof, and recognitions started rocketing, all sprinkled with TV appearances in some of Germany’s most successful cooking shows. In 2016 he was awarded two Michelin stars and a score of 19 of 20 points by Gault Millau who also named him German ‘Chef of the Year’ in 2020.

The pandemic brought Werneckhof to a close but that did not stop Nakamura. At the time, he launched his own pop-up restaurant, the Salon Rouge, and he had great success with a fried chicken takeaway, but he reached the pinnacle of his career when he opened Tohru in der Schreiberei in 2021 and quickly regained the two Michelin stars he held at Werneckhof.

Touching The Heart Of Munich

Tohru in der Schreiberei is located in one of Munich’s oldest townhouses, just a stone’s throw from Marienplatz, where the impressive neo-Gothic New Town Hall stands. The Stadtschreiberei is a late mediaeval three-story building that was rebuilt in 1552 as the city clerk’s office, so it became a nerve centre of power in the city, but it also was a wine storehouse.

Five centuries later, the basement houses a walk-in wine cellar and two spacious rooms for private parties, while on the street level you can spend an evening on the beautiful terrace sipping a Japanese sour, the signature cocktail made with sake, lychee liqueur, lime and yuzu foam, or an excellent Negroni if you prefer the classics. When drinks are finished, a comfortable, easy and unpretentious brasserie-style dinner can complete the experience in the courtyard. Oysters as an aperitif, a refreshing selection of tartars – the carrot tartar is a must – a comforting pork belly with sweet potatoes and wild broccoli or turbot with parmesan risotto, pak choy and shiitake mushrooms are dishes to be shared in this enchanting private garden.

But the gem of the Schreiberei awaits on the first floor, on top of the himmelsleiter, a mediaeval architectural particularity from some Munich old houses that can be translated as stairway to heaven.

Cooking Before Cooking

On a normal day, Tohru and his team would have been working in the mise en place since 12:00. At this time the energy is high in the kitchen, a dozen chefs are chopping, peeling and simmering to the rhythm of techno music. The atmosphere is one of anarchy in order, in contrast to the serene mood guests will find in the evening when they are invited to visit the kitchen.

Tohru stands in front of his station, in the centre of the room, slicing char sourced from the Birnbaum fish farm, just one hour away from Munich.

“The Birbaums do an amazing job with char and all kinds of salmonids on their farm. This char is almost three years old, something you can’t get from any other farm, and that means the fat is better absorbed into the flesh, resulting in better flavor and texture,” Tohru explains.

The Birbaums have been farming fish for three generations, and their work takes place in a bucolic setting of several ponds that mimic the natural conditions in which fish grow.

Founded in the 1960s by Nikolai Birnbaum’s father, who is now passing the baton to his daughter Lea, the place looks more like an Impressionist garden by Renoir than a farm. Flowers and buzzing insects, the delicious aroma of slowly smoked eels, huge sturgeons and rainbow trouts and a constant flow of bubbling spring water create a fairytale setting unexpectedly close to Munich. It’s the kind of place any child would want to grow up.

“They serve the best fish and select it for us when it is at its best, so it is like cooking before cooking,” says Tohru, with unwavering confidence in the Birbaums.

With Sustainability In Mind

The Birbaums are not the only producers with whom Tohru Nakamura has built a long-term relationship of trust. He buys pork chin, once sourced from iberian pigs from Spain, from Herrmannsdorfer, who now sells this unusual cut for Germany just because Tohru asked for it.

Herrmannsdorfer Landwerkstätten is not your typical pig farm. It is an organic country state with an integrated approach to food production. They mainly produce pork and chicken, with an emphasis on humane treatment of the animals, and include a butchery, a bakery, a beautiful restaurant, a brewery, a grocery store… The farm is also a magnet for locals who want to shop, eat in the restaurant or just go for a walk, and Tohru has a strong connection with it, as he spent some time learning at the restaurant when he was a teenager and the farm was also where he celebrated his wedding.

Tohru sources most of the vegetables he uses, such as the beautiful and delicate daylilies, from Johannes Schwarz, the gardener who runs Kinara Gemüse just 30 minutes from the Schreiberei. Again, a beautiful place, run by a conscious expert who goes way beyond the needs of Tohru and the other Michelin starred chefs he works with.

Tohru Nakamura Writes Omakase In German

The Japanese term ‘omakase’ literally means to put yourself in other people’s hands. While when it was first coined, in the 90’s, it was taken to mean that the diner did not care about paying a hefty bill the term is now used to mean something more profound.

‘Omakase’ means ‘you are an expert cook who knows what is in season and how to cook it, so please take care of me: ‘I trust you’.

When you consider how carefully Tohru sources the ingredients for his dishes, how closely he works with producers, and that he has designed his menu according to the ‘kaiseki’ philosophy – meaning that dishes follow a certain order and rules to make the stomach happy – it’s fair to say that he is writing ‘omakase’ in his context, using local ingredients, fusing techniques learnt in Europe and Japan, but with a freedom of expression that would probably not be possible in the Land of the Rising Sun.

The menu consists of nine savory dishes and two desserts. Some are named after their producers, such as the Tarbouriech oyster with daylilies, XO and carrots, an unusual combination of ingredients that worked so well, as the sweetness of carrots turned out to be an excellent accent to the lightly grilled oyster.

Other dishes are named after traditional Japanese recipes, such as the extremely silky, infused with umami flavor, Chawanmushi, or Japanese steamed egg custard, served here with an outstandingly well cooked Oosterschelde lobster, courgette and horseradish.

The Hitomebore is a type of rice that gave its name to the most perfect bite of uni-nigiri I’ve ever had. To be precise, this is not a nigiri but a perfectly balanced base of soft warm rice topped with luxurious sea urchin beautifully crowned with a small flower carved in ginger, served with a Beurre blanc cooked with sake, added Shiokoj and créme fraîche. It is the perfect example of Tohru’s style and precision on the plate, of his undeniable Japanese influence and his way of paying homage to the purity of flavors. The rice melted in my mouth and the uni melted with it, leaving a long, marine and pleasant finish.

Then came the Birnbaums char with kohlrabi, buttermilk and dandelion; the hamachi with cucumber; a spectacular dish of bread – yes, just bread – with Wagyu from renowned farmer Muneharu Ozaki; the skate; the long-awaited Herrmannsdorf pork chin with Royal Belgian caviar, cauliflower and meadowsweet; and a stunning final savoury dish of sweetbread, peas, ‘nduja, anchovies and shiokoji.

The sweetbread, tender and crunchy, perhaps reminiscent of the fried chicken he cooked during the pandemic in his street food adventure, mixed with anchovy and nduja, once again brought out Tohru’s undeniable duality, his double nature, that which surprises and comforts at the same time, without stridency, without wanting to be the protagonist, but putting his technical knowledge at the service of your taste buds and your stomach.

Tohru is not afraid of unusual combinations, nor of fusing European flavors with an underlying kaiseki philosophy. It isn’t Japanese, and yet it was, and it isn’t European, but there are so many local ingredients in it. His culinary seal is not pure, but crossbred, with German and Japanese precision, yet the freedom to break the rules and mix everything together to create something recognisable, but still without a name.

The okashi – desserts – section isn’t only beautiful. It’s fun and a very special moment. As the sweet wines flow, a large tray of petit fours arrives at the table leaving guests to wonder: is this a mistake? No, it isn’t. It’s a moment to pause, share and enjoy a variety of sweet bites full of technique, references to Tohru’s childhood and, once again, his Japanese-German DNA. They were not too sweet, but perfectly balanced. The myoga –Japanese ginger– is a refreshing combination of white chocolate and kir royale, the umami sablé of black sesame and blackberry is intense and the matcha dorayaki – with Doraemon’s face on it – was delicious and fun, as desserts should be.

“In Japan, people specialise in perfecting one dish, be it ramen, sushi, tempura or something else. Here in Germany, I have the freedom to express myself through many different dishes, flavors and techniques, and I found that beautiful,” Tohru points out.

A Devoted Establishment

Tohru in the Schreiberei is all about teamwork and Tohru Nakamura has selected a stellar team based on three key positions.

Dominik Schmid “Smitty”, a long-time companion, is Tohru’s head chef. Restaurant manager Alexander Will will make sure that everything is in its place and will welcome you with the warmest smile, and Christian Rainer -2021 Michelin Best Dining Room Director- will generously pour the finest Chardonnays from Burgundy, Verdicchios from Castelli di Jesi, Palominos from Jerez, Champagne, Sake, Tuscan Sangiovese, Sauternes, Riesling… a silent exhibition of liquid knowledge.

And yet, a whole team will be practising the art of “omotenashi”, another Japanese term that describes taking care of guests with all one’s heart and thinking beyond their needs.

The orange brûlée room is designed to be welcoming, the lighting makes each table feel like a chambre séparée and when guests sit down in the comfortable chairs they will find a beautiful purple envelope and a menu inside, often with with their name on it, a small detail intended to make them feel cared for.

A Reluctant Goodbye

The Japanese principle of ‘nagori oshii’ is the cultural reluctance to say goodbye and standing until your guests have left shows them how much you value the time you have spent with them.

“One of the latest improvements we have made has nothing to do with food or cooking. We accompany our guests down to the street, have a little chat with them before they leave and just stay there until they are out of sight. And it turned out that it creates an intimacy where they express themselves, whether it is what they liked most about the meal or if there is something that can be improved, it’s very nurturing for us and also a way to show our guests gratitude and respect”, says Alexander Will.

Tohru in der Schreiberei is all about these kinds of details –sourcing the finest local ingredients when they are in season, creating the most comfortable atmosphere, putting guests in the centre…– that makes you feel like you can trust them to take care of you and touch your heart.

And whilst putting something as fragile as a human heart into someone else’s hands is a big decision, at Tohru in der Schreiberei it’s clear: Omakase, bitte.

Tohru in der Schreiberei

Burgstraße 5, 80331 München, Germany

www.schreiberei-muc.de

Thank you for consistently delivering top-notch content!