Álvaro Clavijo is the chef behind El Chato, the successful contemporary bistro in Bogotá where a new chapter of Colombian cuisine is being written. He has made it his mission to redefine the local flavors by exploring his country and the endless list of produce it can offer, and through that, has become one of the best restaurants in Latin America.

Obsession can be an endless source of energy that results in great things. In the case of chef and restaurant owner Álvaro Clavijo, being obsessed with always doing things better and with discovering the infinite list of produce that his native Colombia has to offer has turned into the great success of El Chato. One of the two restaurants in his country to be included in the list of The World’s 50 Best—in the 80th spot—and in 2020 as a remarkable 7th in the same list for Latin America.

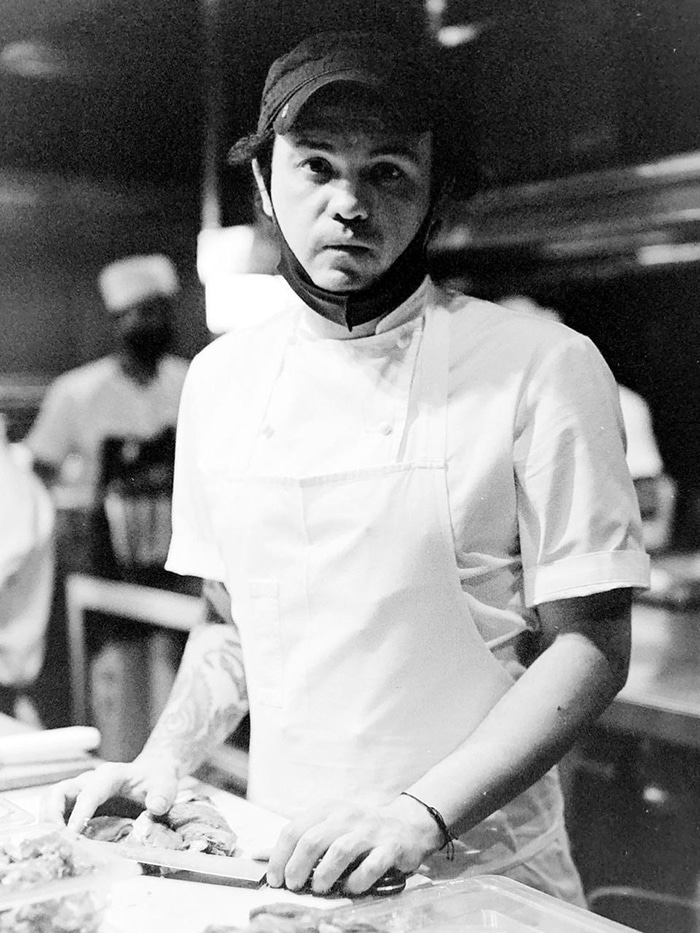

Clavijo attributes that success to his years of experience, that started as a dishwasher in Paris and took him all the way from Barcelona, back to Paris, to New York City and Copenhagen. To that and to an infinite curiosity that makes him go against the norm, that makes him go after problems and take harder ways, but that always results in wonders. It always results in dishes that reeducate the local palate, that put flavor first and that are created to highlight the ingredient.

In that way and little by little, he’s creating a new and exciting Colombian Cuisine at El Chato, a name he chose because it’s a term of remembrance used by rolos, the people from Bogotá, and that represents the love for his history and his intentions to honor it by finding new and exciting ways to highlight Colombian flavors.

Respect for Work

Álvaro Clavijo has a great respect for work. He does, because since very little his mother made him learn its importance and because he saw and enjoyed the results of doing it himself, like the 30 dollars an hour he got paid on a summer job in Washington DC. At only 17 years old and right after finishing high school, he had the opportunity to move to Nice, in the south of France, with his mother, her husband and the whole family. Instead he decided to go by himself to Paris to work and through a friend of her mother got a position as a dishwasher in the tiny kitchen of a Tex-Mex restaurant.

“It all started when I was 17 years old in Paris, washing dishes in a Mexican restaurant. I wasn’t very good at doing that job and the team always got out later because of me, so at one point the chef offered to teach me how to cook and put someone else in that position. He was my first mentor and taught me a lot of things. I started to expedite service and that’s how it all started. At that point I fell in love with everything inside of that kitchen. The noises, the adrenalin, the heat, the screaming, the service, everything. So they hired a new dishwasher and I became a cook.” explains Álvaro.

That restaurant was all about volume, a rough environment where his coworkers used the microwave as one of the main tools during the service but that ended up becoming the place where he would come face to face with his passion for the culinary world. The change from dishwasher to cook worked perfectly and the new urge he had was to become as good as the other cooks in the team, who Clavijo describes as work machines, and to learn.

Change of Plans

In Latin America a lot of young men and women take a year to live abroad, learn or perfect a second or third language, and get some life experience. This was the plan for Álvaro’s year in Paris but it was always supposed to end so that he could come back home and go to university to study architecture, and so he did, or at least tried. A semester was enough for him to realize that there was no coming back from the adrenaline and intensity of the kitchen, and after a serious talk with his mother, he packed his bags again and moved to Barcelona to study in the prestigious Hofmann Culinary School.

Those years at Hofmann and particularly his mentor there, Lluis Rovira, were the first real responsible for Álvaro’s career in fine dining. It was Rovira who forced the then student to try new ingredients, new dishes, to improve his technique, to be curious, to let go of his traditionally sweet Colombian flavors and to explore. And if you combine that motivation with an energetic and obsessive determination, and a love for hard work, the result is someone ready to start at the highest level of the culinary world.

After his studies he worked at the school’s restaurant, did a small internship at the Arts Hotel with Sergi Arola, went back to Paris where he spent one and a half years at Le Bristol and another year at L’Atelier of Joël Robuchon and then moved to New York to join Thomas Keller and his team at Per Se, followed by a season with Matt Lightner at Atera and a final three-month stage at Noma in Copenhagen. An amazing era of experience condensed into one paragraph and that Clavijo breaks down like this: “France gave me my foundation, The States thought me how to be organized and Denmark gave me the beginnings of what ended up becoming my own style.”

El Chato Ep. 1

After Noma, Álvaro returned to Bogotá and had to make a decision: To take a job in Moscow or to stay home and try his own luck. The choice was clear and with no direction or idea of what his new project would look like, he put together everything he had, found a house that was equipped for catering, bought some chairs from a hair salon and tables from a coffee shop, and opened the first El Chato.

“Ever since I worked with Matt Lightner I knew I wanted to go back to Colombia. I knew and felt that I wanted to open a restaurant but I wasn’t sure how to go about it. I had no idea. So much so that two weeks before opening the restaurant we changed the entire menu that we had developed because it did not have any style or make any sense. It was a mixture of food from Morocco, Turkey, France, India, from everywhere but without a style. I didn’t even know what the place was going to be called.”

Right before the opening the mix of pressure and creativity made him think of his concept. He took inspiration from three Colombian cookbooks, and going through the recipes he decided that he wasn’t going to be doing traditional dishes with a twist, instead he was going to highlight those ingredients that make Colombian cuisine special, like de guasca leaves used in the traditional ajiaco soup, and use them for new and different preparations.

“I had never worked with Colombian ingredients and at that moment I said: I am going to complicate my life and I am going to do what I like to do but only with Colombian ingredients. In France I worked a lot with offal and insides of animals. For example I used to make a tête de boeuf terrine al Le Bristol, where every cut of the animal was used. That also reminded me of my grandparents and how they used to eat. It was common Colombian mountain food but people don’t eat that anymore, they focus on premium cuts and i was ready to bring them back”

A Flavor Rebel

The beginnings of El Chato weren’t as glamorous as the present and the tables were empty. At that time chef Álvaro Clavijo had to adjust his dishes to make things more commercial and approachable, but still maintaining his values and the principle of working with Colombian produce prepared using all the techniques he learned in the best restaurants in the world, and most of all, maintaining his idea of doing things differently, of redefining and educating the local palate.

For him it wasn’t an option to give into the usual sweet flavors of local traditional cuisine, as Alvaro is more of a sour and bitter kind of guy. If you ask him where that comes from he will not give a romantic answer nor a childhood memory of him eating fermented fruit or a bitter veggie, he will simply admit that he likes those kinds of flavors just to go against the grain. A risk that he took with intelligence by finding the perfect balance between the commercial and the rebellious, and that paid off with a great response from the public, critics and press.

“The Colombian palate is very sweet. Here people are happy with a fried ripe plantain, but let’s say that I always wanted to go against that. I am more acidic and bitter. It’s about curiosity and discovering new things. It would have been easier to serve a honey-glazed pork that makes locals happy, but I don’t like the easy, obvious way. That’s also why I don’t allow changes in my menu, just to pleaser the easy way. In a way, just like my mentor Lluis Rovira made me try things and open my mind, many people leave my restaurant surprised by what they ended up trying. It becomes an educational approach that we have also imposed on ourselves.” explains Álvaro.

A great example of that is a dish that has been on the menu since the beginning and they haven’t been able to take out; chicken hearts with richy potatoes and suero costeño, a very salty fermented dairy from northern Colombia. First they confit the hearts, which they have to clean and massage individually first, and then regenerate them on a pan right before plating them with the buttery potatoes, a Chimichurri sauce made out of sorrel stems, pickled onions, chili, sorrel leaves and egg yolk.

El Chato Ep.2: A Contemporary Bistro

By 2017 the project outgrew the humble house where it all started and El Chato moved to a nicer area. A bigger and more thought out location that responded to the success and the demand of the guests but that maintained its DNA. A contemporary bistro, an unpretentious but exciting restaurant that guests could visit even several times a week, without a tasting menu, with a casual feel and where dishes change depending on the produce available. Examples of those dishes include the cornbread with kefir butter and honey; squid with avocado, cress leche de tigre and guatila; or the pork cheek with plantain, cabbage in butter, miso and shiitake.

“I’m always asked what kind of food we make at El Chato and it is very difficult to give that definition. The only thing I can answer is that we take inspiration from local suppliers and from there we build a dish that people can order à la carte, so the best way to name it for me was a contemporary bistro. I didn’t want a white tablecloth restaurant. I wanted good, tasty food, a place that people want to return to several times a week instead of once every six months, and it seems like that has played a big part in our success”.

That constant change in the menu is both an opportunity and a challenge for the Colombian chef. It works as motivation for him to bring the best out of a country that’s ready to be discovered after decades of political instability, but also means that he and his team can never stop creating and working at 100%. That formula became the final stepping stone towards international recognition and in 2018 El Chato entered The Latin America’s 50 Best Restaurants list at number 21, also winning the award for the highest new entry.

A produce a dish

The drive of Álvaro Clavijo to introduce his guests to amazing Colombian produce is what makes this project special for him . It makes him explore his own country. He sometimes has to go the extra mile to convince a farmer to change his ways or grow a new veggie or fruit. In the case of one of his staple dishes, the baby corn cob with butter mayonnaise, fresh cheese and toasted corn, the chef even had to cook for the farmers to make them understand the difference between the cobs when they’re 42 days old and when they’re fully grown.

“In the case of corn, our suppliers sell it by weight. He preferred to let the cobs grow and sell them more expensively and I had to go to his land, explain what we wanted to do and convince him to change his way of working with the product and selling it. We reached an agreement to buy them per unit and I even had to cook with their cubs. When trying them, he flipped out and understood our idea. I wanted to use it so much that I went to all these turns to achieve it. That is part of the challenge with our suppliers and the restaurant. For example potatoes, or carrots. They don’t grow colored carrots because nobody buys them. We are losing variety against the most commercial produce. Luckily this is changing and people are trying new and different things” explains Álvaro.

For this dish, another one of the very few that have been on the menu since the beginning by popular demand, the baby corn cobs are grilled over charcoal and then finished with a mayonnaise made out of butter that adds tons of flavor and tends to cut when served. The finishing touches are grated fresh cheese, purslane, chives and jalapeño. A vegetarian dish inspired by Colombian street food but elevated using El Chato’s two principal values: Curiosity, the best Colombian produce – and technique applied in a democratic way.

El Chato, Calle 65 # 4-76, Bogotá, www.elchato.co

Only rich Colombianos live abroad for a year to just learn another language or to see other cultures. Colombians who leave their beautiful country is 99% of the time to work and live better, not just because.