Learn how to fabricate a whole chicken and then use the whole bird in a cost effective and delicious way.

By Sofia Eydelman

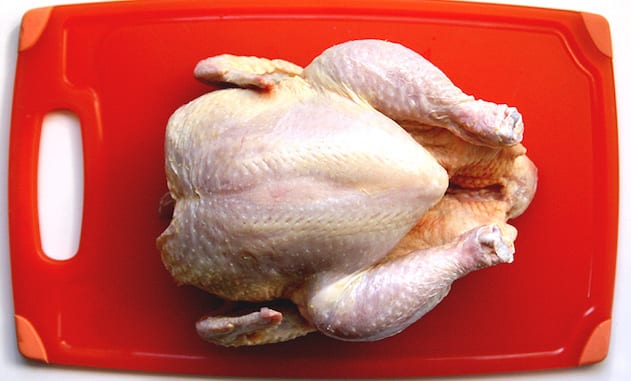

For many people, picking up a whole chicken can be intimidating or unappetizing, as it resembles the actual bird. For others that are okay with the animal resemblance, the barrier may be not knowing what to do with a whole chicken, or thinking that it takes a long time to prepare. Whatever the case may be, very few people buy whole chickens and I’d like to change that. There are benefits to doing so and I’m hoping that a little guidance and inspiration can nudge some of you in that direction.

There are many great things that you can do with a whole chicken without even having to cut it up. Roasting or smoking it whole are the most popular methods at home, but we’ll also occasionally do soups or stews. I want to start with a step by step guide on how to break up a whole chicken into the parts that you would normally see sold separately.

THE BENEFITS OF BUYING A WHOLE CHICKEN

The most obvious benefit to buying a whole chicken is that it’s cheaper, provided that you value all of the different parts. The cost savings will vary depending on the source of the chicken and in my case its significant.

Y’all know I love a little math so I broke out the calculator to do a comparison. A whole chicken, roughly 3.5 lbs, from my grocery store cost $15 + change. I took note of the prices per weight of the individual parts that I was going to cut it into (skinless boneless breast, leg quarters, and wings). Once I cut the chicken, I weighed the individual parts and multiplied those numbers by the respective prices. Had I bought those chicken parts separately, they would’ve cost almost $22!

My favorite part about cutting up a whole chicken is having the bonus of bones and wing tips to make into stock (Get the stock guide here) and excess skin and fat to render, but it still makes sense even if you don’t make use of the so called “waste”. The process of cutting a chicken into parts takes about 3 minutes with a good knife and a little practice, so I won’t put a lot of weight on the value of time here.

Another benefit is having more options for sourcing chicken. Farmer’s markets and farms will often only sell whole birds, so having the choice to buy chicken directly from the farmer is the reason that I originally started working with whole chickens. While I still often buy chickens from the grocery store, there are more options for organic and/or locally sourced chickens when buying them whole.

CHICKEN ANATOMY

Before we begin cutting up the chicken, I’d like to point out that there are so many ways of doing this and that there’s no right or wrong way. I’m showing you the way that I’ve learned and the cuts that I prefer. Even in the process of shooting this post, my mom taught me a new and better way to cut off the wings. So whatever you see here, use it as guidance, but be open to different and better approaches.

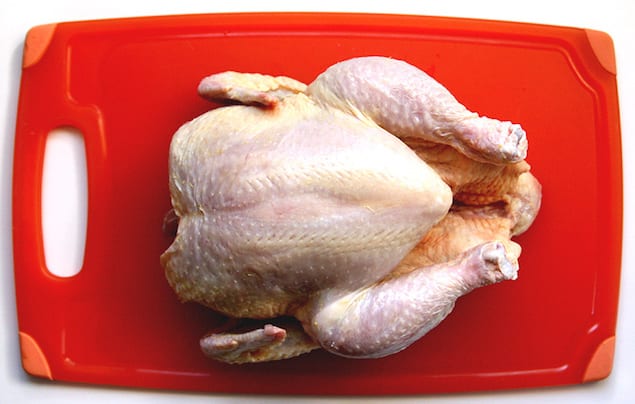

STEP 1: PREPARE THE CHICKEN

Check the cavity for a baggie of livers/kidneys and/or a neck. Remove everything from the cavity, rinse the chicken, pat it dry, then trim off any excess skin/fat near the top or base of the cavity. I reserve the neck for soup, collect the skin/fat for rendering, eat the liver, and give the kidneys to my dog.

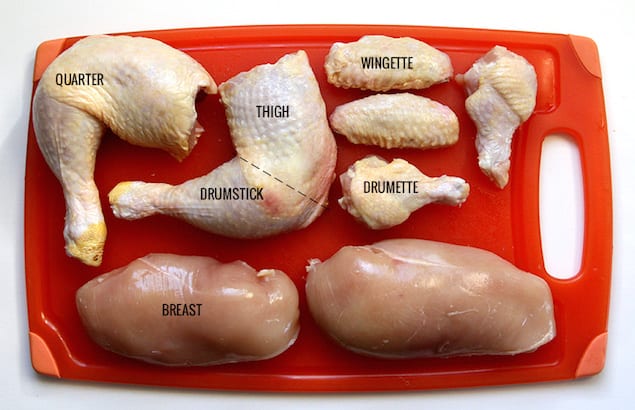

STEP 2: DETACH THE LEG QUARTERS

Start by slicing through the skin between the breast and the inner thigh to loosen the leg quarters (leg quarter = thigh and drumstick combo). Grip the quarters firmly and open them outward to snap the joints that connect the thighs to the back and expose the bone. Once the joints are detached, turn the chicken on its side, and use your knife to slice along the back of each leg quarter, taking care to pass the knife through the joint where it was separated. This takes a little bit of fiddling and practice, just know that you shouldn’t be cutting through any bones or joints here, and that the key is to locate where the joint has already been separated and cut through that point.

I prefer to leave the quarters whole, but you can continue to separate them into drumsticks and thighs (similar to instructions for separating wings below).

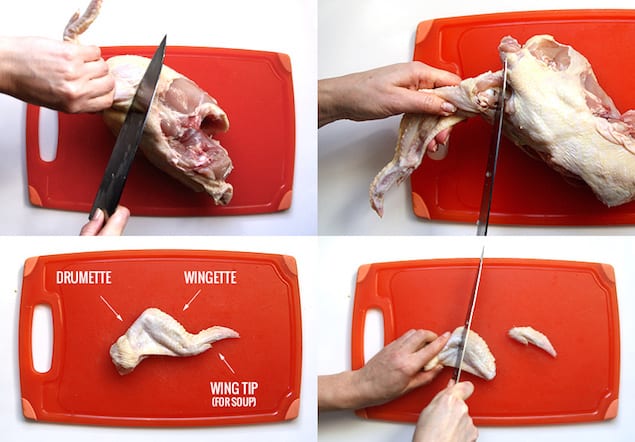

STEP 3: DETACH AND SEPARATE THE WINGS

Slice the skin at the base of the wing, near the “armpit” part that connects the wing to the breast. Once you’ve cut through the flesh leading up to the joint, rotate the wing to snap the joint that connects the wing to the back, exposing the bone. Continue cutting off the wing, passing your knife through the separated joint, similarly to how you detached the leg quarters. Repeat the process with the second wing.

You can leave the wings whole but I prefer separating them into three parts – the wingette, the drumette, and the wing tip. The first two parts are the common ones you get when having chicken wings. The tips can be reserved for soup.

To separate them is a little trickier, as you’re not snapping the joints. The trick here is to locate the spot with soft cartilage in each of the joints and cut through there. It takes a little guessing and practice, but once you’ve done it a few times, you’ll know where to cut just by looking at the wing.

STEP 4: CARVE OUT THE CHICKEN BREASTS

You’re almost done and this is the easiest part. Locate the long breast bone of the chicken, between the two breasts. Starting with one side, slice your knife along that bone, as close to it as possible, then use your hand to gently separate the breast meat from the carcass. Use your knife to cut through whatever meat isn’t easily pulled off by hand. Repeat the same steps with the second breast. Manually pull off the skin if you wish. I reserve it and render the fat.

STEP 5: FREEZING (OPTIONAL)

The image below shows one chicken, for clarity, but freezing works best when you’re working with a few chickens. I usually do 2-3 chickens at a time, simply because I can portion them better for our meals. Scale your operation depending on the types of portions that you need.

Group the parts (including bones and wing tips) and freeze in ziplock bags for your future chicken adventures!

Many stew-like recipes will call for a whole chicken cut up into parts, but I prefer to cook the white (breast) meat and dark (thigh/leg) meat separately. If you are making a stew recipe that calls for a whole cut up chicken you can use the thigh/leg meat from two chickens, freezing the breasts for another use. I would strongly suggest saving the wings to eat as just wings. They’re SO much better not in a stew.

Very helpful, thank you. :)

where is the tenderloins ???

LOOKS LIKE THIS IS A GREAT SITE TO TRY. THANK YOU.

BECKY

This is so great thanks! Your pictures really break it down. People spend so much on chicken parts yet the whole bird gives so much more like you mentioned, soup time – like the French do, making use of all parts.

This is same way my mother taught us. I never buy canned broth. One carcass makes a whole pot.