The Armenian people are ancient, and so is their cuisine. And while Armenians have often in history been dominated by outsiders, most foreign overlords historically didn’t dictate any changes in Armenian food traditions.

The Soviet period, which lasted from 1922 to 1991, was different. With its penchant for command economy and total regulation of life, it uprooted many long-established food customs. Armenia’s ancient heritage as a winemaking country was set aside for brandy production, and many of its traditional dishes were lost; pork in large part replaced the beloved lamb, and industrial bread displaced traditional oven made bread, among other drastic changes.

But lately, many Armenian chefs, gastronomes, researchers and restaurateurs are turning to old memories- some written, some not- to recover ancient traditions and renew the Armenian table. Some are delving into manuscript archives to recreate the Armenian cuisine of yesteryear to enrich their contemporary culinary imagination. Others are gathering vernacular food traditions in field-work.

“There are many manuscripts in the Matenadaran that I would love to explore,” says Chef Davit Poghosyan of Mov, a lovely space on Pushkin Street in the centre of Yerevan which offers an exquisitely creative take on traditional Armenian cuisine. “I am deeply interested in learning about how Armenians lived in the past and understanding what they cooked in their homes. It is especially important for me to gain insight into their way of life, as it inspires me to create new dishes that pay tribute to my ancestors and honor their legacy.”

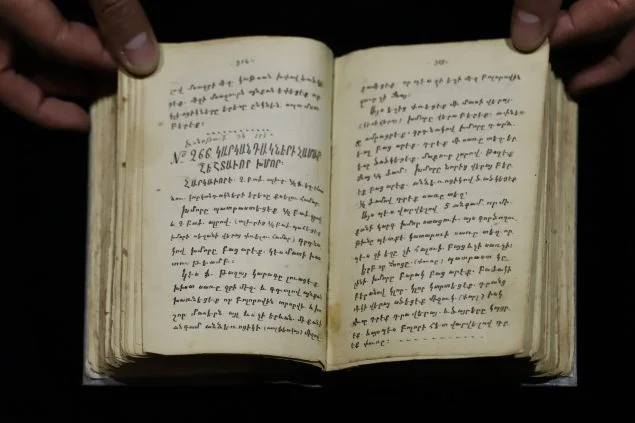

The Matenadaran, Armenia’s national manuscript museum, rests against a rocky hill in the north of central Yerevan. It is at once an archive and a shrine to the ancient and tenacious literacy, and the ancient and tenacious identity of the Armenian people.

It is in a way a secularized monastery, its original deposit of manuscripts having been transferred from the holy see of Echmiadzin. Built in 1959, it is reminiscent of a Loos building, austere on the outside, with a warm and polished interior. It enjoys a commanding view of Mashtots Street, named after the polymath sage and inventor of the Armenian alphabet, Meshrop Mashtots, whose statue sits at the foot of the institution. In its vaults there are all sorts of treasures, from all over the world; it is the incarnate memory of Armenia, with its long and cosmopolitan experience. Amongst its many gems are some antique culinary manuscripts, some in code, perhaps to stymie invaders, perhaps to stymie rivals.

Mov

Chef Davit Poghosyan at Mov is passionate about showing the world the spirit of Armenian cuisine. He says he discovered his passion for cooking in his grandmother’s bakery as a small child. Antique Armenian cookbooks are among his foremost guides in his work of rediscovering and renewing classical Armenian dishes.

Mov dolmas are outstanding, and especially notable among them is their Udoli Tolma, a traditional dolma made with whole lamb chop, bulgur and mint, local tomatoes and clarified butter, and rolled in grape leaves. The recipe Mov uses originates, Chef Davit says, in a manuscript held in the Matenadaran, but he hasn’t been able to access the manuscript there himself yet. He acquired the recipe from a colleague who acquired it from Chef Karo Gyumujyan, who Chef Davit says is primarily responsible for recovering the ancient dish. From medieval manuscript to modern table, and the result is delightful.

Agape Refectory

Agape Refectory in Echmiadzin serves up its culinary wonders in a seventeenth century monastic refectory of stone with rib vaults and sconce torches (now electric, of course), it could be a set from Wolf Hall or Game of Thrones; a particularly apt setting for the resurrection of old dishes. Agape carefully honors the history and original monastic table spirit of the place; the name of the restaurant is the New Testament Greek word meaning “brotherly love”.

Hakob Hakobyan is the proprietor of Agape. After years abroad, and some time managing a restaurant in France, he decided to return to his native Armenia and open Agape. Hakob’s passion for traditional Armenian cuisine combines with a historical sensibility enabling him to distinguish phases and changes of traditions over time and in different places.

“The location and history of Agape makes you think about its history. It takes you to where Armenia was, when it was built back in 1655. It makes you think about the people who visited this ancient Refectory, who ate in it, and even lived in it when they did their pilgrimage to the Church. Having all this in mind, we started asking the priests about its history and ancient manuscripts that might keep recipes that had been used during the 17th century. And we were met with a lot of enthusiasm. The priests even helped us in finding passages that described the food back then.”

Hakob says the old manuscripts mostly reflect the cuisine of the clergy, not folk recipes, but that fortunately, despite even the destructive alterations and standardizations of the Soviet period, “what has been lost in the cities, still is cooked/practiced in the towns and villages of Armenia,” so the Agape team diligently research these surviving traditions too.

Keenly aware that food traditions are always a living thing, Hakob says that there is always a process of turning historical inspiration into dishes for the present.

“I’d say that we can never truly recreate the past without inputting a little of our own present into it. Even the manner of how we cook the food is, by necessity, different than they would have done it before. Also, we have access to different ingredients that they wouldn’t have necessarily had access to, also our clients have different, more refined tastes. I would say rarely do we change nothing, but in principle we try to change as little as possible. When we do change something significantly, we call it a “fusion” dish, not an ancient one.”

With partners, Hakob also opened Tnjri and Mshoosh restaurants in the Areni region, and more are to come. Agape is the more historically minded of the projects, in accordance with the hallowed past of its setting. Tnjri and Mshoosh draw inspiration more from regional folk traditions. “For example, we take the ghavurma of Areni and create something new and exciting with it. Like our Tnjri salad. This is more of a fashion of local dishes served in new styles. It can be Armenian styles that haven’t been used with this specific dish or foodstuff or it can be a European approach to a traditionally Armenian product or dish. The emphasis is always on the specific region. As we plan on eventually having a signature restaurant in each region of Armenia, we concentrate specifically on every regions’ specialties.”

Tsaghkunk

Tsaghkunk Restaurant & Glkhatun near Lake Sevan is part of the Gagarin Village project, an enterprise devoted to the sustainable development of the region conserving as much of its traditional land usage and food ways as possible. The restaurant makes its own lavash in a renovated medieval glkhatun, a traditional village headhouse with tonir ovens, just a few paces away from the restaurant,

The Tsaghkunk kitchen is presided over by Chef Arevik Martirosyan, and prides itself on its deeply researched and masterfully prepared traditional dishes. A very special one among these is Amich, an ancient dish of stuffed chicken. Professor Ruzanna Tsaturyan, an ethnographer who has conducted extensive research into local traditions for the Gagarin Village project and Tsaghkunk Restaurant, explains that Amich is so old that it can be dated back to well before the middle ages, to the old Armenian royal court of late antiquity; the earliest attestation, she says, is in the Epic Histories text of the 5th century scribe Faustus of Byzantium.

As the bread flies from the glowing ovens under the vaulted roof of Tsaghkunk’s medieval headhouse, we can expect the experimental fire it symbolizes to warm up and illuminate new life for the region.

Arm Food Lab

In the mountain town of Dilijan, “Armenia’s Switzerland”, Ani Haroutunian runs the remarkable Arm Food Lab, dedicated to recovering food traditions. Born in Yerevan, Ani spent much of her childhood visiting family in the countryside. She says “…my most vivid and beautiful memories are about cooking, eating, farming and enjoying a simple lifestyle.” In 2016, she opened Armenia’s first specialty coffee roaster and soon after, Arm Food Lab and Ootelie Bakery. Ani says, “I didn’t study cooking or baking anywhere, I’m self taught and also much of the knowledge and mastery comes from my mother.”

Ani says that in its mission of recovering old traditions Arm Food Lab uses three kinds of research: historical and documentary research, field research involving “interviewing locals, getting to know local ingredients and their names, trying to track recipes’ historical pathways and understanding the power and potential of a certain area”, and finally, foraging “as a type of research in order to understand and use our country’s rich edible biodiversity with awareness and care”. But Arm Food Lab’s mission goes beyond the gastronomic, and into broader matters of food justice and sustainability. “We’re very focused on food safety and security problems, sustainable local and seasonal produce”, Ani says.

Ani’s vision is to renew Armenian food traditions for everyone. “There are many dishes I’ve discovered during these years and I’ve tried to introduce them in a more modern way. Not in a fancy way, but in a way that is optimistic and can suit modern lifestyle. I’m really proud of my spice mixes (mainly herbs and flowers) and vinegars, because this way I can introduce the Armenian flavor to people more broadly.”

But Ani’s special passion is for baking and bread. “The biggest thing that I’m very excited about now is recovering authentic Armenian bread types, such as Taptapa, and making them popular and known again. The USSR impacted Armenian bread culture as well and people started to eat more commercial bread and very few people bake traditional breads in traditional ovens now. It also resulted in growing mainstream and bred grains with less flavor and nutrients. So I want to explore the whole cycle of bread making from seed to the actual bread and I believe that the future of the bread is in its past!”

These projects of recovering traditional foodways are not merely academic; they are resurrecting the Armenian table for the whole country, nourishing body and soul together. As Armenia charts its way toward its future on its own terms, the inspiring researchers and chefs and restaurateurs working tirelessly to recover lost foodways will doubtless play a great role. Perhaps someday they will even have their own monument at the Matenadaran.